Year after year, beach season brings accounts of harrowing shark attacks as people around the world plunge into the surf to escape summer’s heat.

But the reality is that these fearsome predators kill an average of four people worldwide every year, while humans kill anywhere from 26 million to 73 million sharks annually, according to recent calculations by an international team of scientists.

With the latter toll mounting rapidly in recent years, there has been a growing realisation that something must be done to prevent sharks from disappearing from the planet.

Two weeks ago, Mexico, which has a large shark fishery, enacted a new law that protects three species, bans the practice of shark “finning” – slicing off the fins of a newly caught shark and tossing the animal back in the ocean to die – and requires authorities to monitor the activities of large shark-fishing boats.

Threat

“For most of human history, sharks have been seen as a threat to us,” David Balton, the US deputy assistant secretary of state for oceans and fisheries, said in a recent interview.

“Only recently are we beginning to see we’re a threat to them.”

Unprovoked shark attacks off US shores have risen over the past century, as Americans have flocked to the coasts and researchers have collected more careful statistics.

Yet the number of deaths worldwide has dipped slightly in recent years, according to the International Shark Attack File, compiled by the American Elasmobranch Society and the Florida Museum of Natural History. Occasionally, the number of deadly attacks spikes, as it did in 2000 when sharks killed 11 people.

The declines in shark populations have been steep, as documented recently by scientists using technologies including satellite tracking and DNA analysis.

In March, a team of Canadian and US scientists calculated that between 1970 and 2005, the number of scalloped hammerhead and tiger sharks may have declined by more than 97 per cent along the East Coast, and that the population of bull, dusky and smooth hammerhead sharks dropped by more than 99 per cent.

Globally, 16 per cent of 328 surveyed shark species are described by the World Conservation Union as threatened with extinction.

From Mexico to Indonesia, much of the hunt for sharks is driven by the growing demand for shark-fin soup, a prized delicacy that conveys a sense of status in Asian countries whose citizens are enjoying newfound wealth.

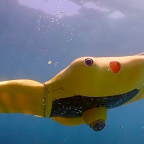

On a recent spring afternoon in the tiny camp of El Chicharon outside Las Barrancas, two brothers, Francisco and Armando Bareno, returned to shore with a catch of two dozen mako and blue sharks.

At the edge of the water, they began slicing off the fins so they could pack them separately onto a truck bound for Mexico City, more than 1,000 miles away.

The fins are so much more valuable than the meat that without the fin market, many fishermen might not bother to hunt sharks at all: The Bareno brothers get 1,000 pesos, or $100, per kg for the dried fins they deliver. The shark meat fetches just 15 pesos, or less than $1.50, a kilo.

Francisco Bareno said in Spanish that he doesn’t really like the work that much. “It’s dangerous,” he said. “But I have to live.”

In recent years, efforts to protect sharks have been driven in part by revulsion over finning. The United States has been a leading proponent of shark conservation, and in 2000, President Clinton signed legislation making it illegal to possess a shark fin in US waters without a corresponding carcass.

Environmental groups are at odds with the Bush administration over the EU proposal to list spiny dogfish and porbeagle sharks under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), a measure on which the United States has yet to take a position. Both species are fished off US coasts: Europeans use spiny dogfish in fish and chips, while porbeagles are prized for meat and fins.

Social Profiles