Beaked whales are disturbed by naval sonar, according to scientists.

A new study suggests that the whales are particularly sensitive to unusual sounds.

Measuring their reactions to both simulated sonar calls and during actual naval exercises, researchers found the whales fell silent and moved away from the loud noises.

The use of sonar for naval communication has been linked to beaked whales stranding in the past.

Scientists from the University of St Andrews, Scotland have been working with marine experts from around the world to investigate how sonar affects beaked whales in the Bahamas.

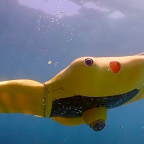

Beaked whales are an elusive group of small whales named for their elongated snouts.

However, they are probably best known for their connection to the possible risks that naval sonar poses to marine mammals.

For example, in 2000 and 2002, large groups of beaked whales stranded and died.

Naval exercises involving sonar communication were taking place nearby on both occasions, raising concerns that the whales’ deaths were directly linked to the mid-frequency signals.

In their study, published in the journal PLoS One, researchers focussed on waters around the US Navy’s Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Center.

Blainville’s beaked whales (Mesoplodon densirostris) have been identified foraging in the area by the navy’s acoustic monitoring equipment, used for listening to signals from submarines.

The scientists listened to the group of whales using these hydrophones – underwater microphones.

During live sonar exercises by the US Navy, the whales stopped making their clicking and buzzing calls, which they are thought to use to navigate and communicate.

“Results… indicate that the animals prematurely stop vocalisations during a deep foraging dive when exposed to sonar.

They then ascend slowly and move away from the source, but they do resume foraging dives once they are farther away,” said David Moretti, Principal Investigator for the US Navy.

Using tags attached to the whales, the team was also able to track their movements with satellites.

They found that the whales moved up to 16km away from the area during sonar tests and did not return for three days.

“It was clear that these whales moved quickly out of the way of the [navy] sonars. We now think that, in some unusual circumstances, they are just unable to get out of the way and this ends up with the animals stranding and dying,” said Professor Ian Boyd, chief scientist on the research project.

To further understand the whales’ behaviour, the team also played simulated sonar calls to the whales, including the calls of killer whales.

The beaked whales showed the same avoidance behaviour in response to these calls.

“It appears that they just don’t like unusual sounds. But the way in which sonars are used to hunt for submarines may mean that the whales are more vulnerable to that type of sound,” said Prof Boyd.

They are known to emit high-frequency calls but this is the first time anyone has proven that they react to mid-frequency sounds.

“We showed that the animals reacted to the sonar sound at much lower levels than had previously been assumed to be the case,” said Prof Boyd.

“Perhaps the most significant result from our experiments is the extreme sensitivity of these animals to disturbance.”

Source: bbc.co.uk

Social Profiles