What has happened at the Cabo Pulmo marine reserve off the southern tip of the Baja Peninsula is fishy – in a good way.

Once severely depleted of fish, the reef system off Cabo Pulmo now teems with marine life, thanks to fishing restrictions imposed more than 10 years ago.

But environmentalists are worried that that ecological advance will be lost if the Mexican government allows a $2 billion development plan to go ahead that would place a “new Cancun” less than three miles north of the Cabo Pulmo marine sanctuary.

Mexico’s Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources has given Spanish developer Hansa Urbana all but final approval for the project, which would turn desert scrubland into a bustling development of hotels, condos, golf courses and a large marina.

The government says such a resort would have no impact on the marine reserve.

That makes environmentalists seethe. They say the secretariat’s speedy approvals are questionable and without scientific merit.

“This development is completely unjustifiable, especially since it’s right next to the marine reserve,” said Alejandro Olivera of the Mexico office of Greenpeace, the international activist group on conservation issues.

Olivera called the revival of Cabo Pulmo, the northernmost reef system along the Pacific coast of the Americas, “one of the best examples of marine conservation in Mexico.”

“These fishermen realized that the waters were being overfished. So they changed from being fishermen to becoming providers of eco-services,” he said.

Their action to halt commercial fishing brought about such a dramatic transformation of the reef system that oceanographers say it’s an example not only for Mexico but also for other parts of the world.

The Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, one of the world’s premier proponents of ocean health, described Cabo Pulmo as “the world’s most robust marine reserve.”

Scientists at Scripps reported in a scientific journal last month that the number of fish in the 27-square-mile marine reserve had soared 460 percent during a recent 10-year period.

“It’s a totally, totally different reef,” said Octavio Aburto-Oropeza, the lead oceanographer for the study. “It’s the most dramatic thing.”

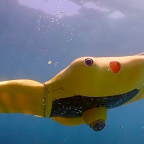

“You go down and you see huge animals: tuna, jacks, sea bass, groupers,” said Brad Erisman, a marine ecologist who was a co-author of the study.

Framed by a backdrop of stunning mountains, Cabo Pulmo sits on the eastern cape of Baja California about 60 miles northeast of Los Cabos, a tourism magnet.

Its 200 or so villagers are descendants of Jesus Castro-Fiol, a legendary diver for mother-of-pearl along the coral reefs on the parallel fingers of basalt that lie partly exposed underwater.

By the early 1990s, as they lobbied the government to declare the reef system a marine reserve, some members of the extended Castro clan began offering kayak expeditions, snorkeling trips and reef dive adventures to visitors. Today, the village has a half-dozen dive and snorkel shops.

The move toward sustainability didn’t stop there. The village declined to hook into the national electrical grid, choosing to rely on solar panels for power.

A smattering of Americans have bought lots and built homes in Cabo Pulmo, supporting a handful of restaurants, and a steady trickle of tourists arrives along the gravel road that connects to the outside world.

While villagers chose new livelihoods, the fish population boomed, and big predators such as tiger and bull sharks, marlin, tuna, wahoo, snapper, grouper and sailfish also thrived.

The predators caused smaller species to reproduce more quickly, strengthening the entire marine ecosystem.

Social Profiles