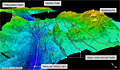

US scientists have mapped the deepest part of the world’s oceans in greater detail than ever before.

The Mariana Trench in the western Pacific runs for about 2,500km and extends down to 10,994m.

This measurement for the deepest point – known as Challenger Deep – is arguably the most precise yet.

The survey, conducted by the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping (CCOM), was completed to help determine the exact extent of US waters in the region.

“We mapped the entire trench, from its northern end at Dutton Ridge, all the way to where it becomes the Yap Trench in the south,” explained Dr Jim Gardner from CCOM, which is based at the University of New Hampshire.

“We used a multibeam echosounder mounted on a US Navy hydrographic ship. This instrument allows you to map a swath of soundings perpendicular to the line of travel of the ship. It’s like mowing the grass. And we were able to map the trench at a 100m resolution,” he told BBC News.

The distance to the bottom of Challenger Deep has an error associated with it of about plus or minus 40m.

The figure of 10,994m is slightly less than some other measurements in the modern era, but they are all broadly similar.

A location in the trench about 200km to the east of Challenger goes almost as far down. This spot, known as HMRG Deep, has a depth of 10,809m.

It is extraordinary to think that both Challenger and HMRG extend deeper below sea level than Mount Everest rises above it.

Dr Gardner said his team’s survey put a huge effort into getting the “sound speed profile” of the water column correct – this measure of how the echosounding signals curve as they descend is the largest source of error in the measurement.

He presented the results of the mapping here at the 2011 American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, the world’s largest annual gathering of Earth and planetary scientists.

The US State Department funded the study because it wants to know whether the exclusive economic zone encompassing the American territories of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands can be pushed out beyond its current limit of 200 nautical miles (370km).

This may be possible if the shape of the seafloor fulfils certain requirements under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

But the data also has high scientific interest in that it gives geologists a clearer picture of the structures in one of the most fascinating subduction zones on Earth.

It is at the trench where a huge slab of Pacific oceanic crust is diving down under the adjacent Philippines tectonic plate.

Researchers are keen to know what happens when underwater mountains, or seamounts, go over the edge and are swallowed.

There has been considerable debate over whether the descent of the seamounts can influence the frequency and scale of big earthquakes. It has been suggested they might create extra friction that can then be released suddenly to trigger major tremors.

“Our data shows the seamounts entering the Mariana Trench are getting really fractured as they go down,” said Dr Gardner.

“As soon as the Pacific Plate starts bending down, it cracks that old, old crust. That crust is really brittle. It cracks right through the seamounts. Certainly in the Mariana Trench, the seamounts get splintered and whittled away, and then get subducted.

“What I don’t see are remnants of seamounts being accreted to the inner wall of the trench.”

What is evident, however, is the pile of material this creates across the axis of the trench in a number of places. Dr Gardner describes four “bridges” that stand as much as 2,500m above the floor of the depression.

‘Race to the bottom’

The survey is also highly topical in that four teams are about to send manned submersibles into the trench to explore its depths.

So far, only two humans have visited Challenger Deep – Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard in the research bathyscaphe Trieste in 1960.

Social Profiles