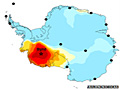

A new analysis of temperature records indicates that the Western Antarctic Ice Sheet is warming nearly twice as fast as previously thought.

US researchers say they found the first evidence of warming during the southern hemisphere’s summer months.

They are worried that the increased melting of ice as a result of warmer temperatures could contribute to sea-level rise.

The study has been published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The scientists compiled data from records kept at Byrd station, established by the US in the mid-1950s and located towards the centre of the West Antarctic ice sheet (WAIS).

Previously scientists were unable to draw any conclusions from the Byrd data as the records were incomplete.

The new work used a computer model of the atmosphere and a numerical analysis method to fill in the missing observations.

The results indicate an increase of 2.4C in average annual temperature between 1958 and 2010.

“What we’re seeing is one of the strongest warming signals on Earth,” says Andrew Monaghan, a co-author and scientist at the US National Centre for Atmospheric Research.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to determine that there’s warming going on during the summer season.” he added.

Top to bottom

It might be natural to expect that summers even in Antarctica would be warmer than other times of the year. But the region is so cold, it is extremely rare for temperatures to get above freezing.

According to co-author Prof David Bromwich from Ohio State University, this is a critical threshold.

“The fact that temperatures are rising in the summer means there’s a prospect of WAIS not only being melted from the bottom as we know it is today, but in future it looks probable that it will be melting from the top as well,” he said.

Previous research published in Nature indicated that the WAIS is being warmed by the ocean, but this new work suggests that the atmosphere is playing a role as well.

The scientists say that the rise in temperatures has been caused by changes in winds and weather patterns coming from the Pacific Ocean.

“We’re seeing a more dynamic impact that’s due to climate change that’s occurring elsewhere on the globe translating down and increasing the heat transportation to the WAIS.” said Dr Monaghan.

But he was unable to say with certainty that the greater warming his team found was due to human activities.

“The jury is still out on that. That piece of research has not been done. My opinion is that it probably is, but I can’t say that definitively.”

This view was echoed by Prof Bromwich, who suggested that further study would be needed.

“The tasks now are to look at the relative contributions of natural variability,” he said.

“This place has very variable weather – some of it is influenced by human acts and some of it isn’t. I think its premature to answer that question right now.”

Whatever the source, the researchers are concerned that this warming can lead to more melting and have direct and indirect effects on global sea levels. The direct impacts are the run-off of melting waters into the sea.

But the scientists say this is unlikely to happen for several decades because much of the water is likely to percolate down the ice sheet and refreeze.

Glacial pace

The indirect effect is that it can “pre-condition” the ice shelves that float at the edges of the ice sheet. The scientists say that this is what happened in 2002 on the Antarctic peninsula when the Larsen B shelf collapsed spectacularly in just a month.

“The melt water went down into the crevasses and filled them up,” Dr Monaghan said.

“Just like a pothole in the road in wintertime, the water will freeze and expand and break it apart.”

Social Profiles