Scientists working on a Nasa-led project are scanning large swathes of the Great Barrier Reef as part of the biggest assessment of the world’s coral reefs ever undertaken.

The US$15m three-year coral reef airborne laboratory mission promises to solve outstanding mysteries of what drives coral reef health and provide reef managers with better information about how to protect them.

Reefs around the world are still reeling from the worst global bleaching event in recorded history. On the Great Barrier Reef almost a quarter of the coral was lost, mainly in the remote northern sections.

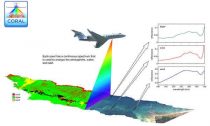

Using a Nasa plane decked-out with a cutting-edge image sensor, Eric Hochberg from the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences and colleagues will examine how much of the area is covered by coral, sand and algae, then repeat the survey at three other locations around the world.

The state-of-the-art image sensor, called the portable remote imaging spectrometer (Prism) was developed by Nasa’s jet propulsion laboratory and is able to capture data across the ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared spectrums, at a level of detail similar to what can be captured from a boat.

From 8.5km above the water, the scientists will be able to see what is happening on reefs at a huge new scale, which would produce a “step change” in how we understand the factors influencing the health of reefs, Hochberg told Guardian Australia.

“Our current surveys, even though we’re doing our very best, it’s easy to miss things,” he said. “You look at a point here and a point there but what’s in between? What we’re after is to get the complete picture.”

Hochberg said pollution was known to hurt coral reefs but researchers had had trouble pinning down the connection. He said part of the impetus for the new survey came from an analysis he had done of reef health and human impacts, which could not find a clear link. “That’s part of what convinced Nasa to support this project,” he said.

Hochberg said by studying vast sections of reefs at once the team would be able to compare a lot of different areas without missing sections.

Part of the research has involved developing an algorithm that lets scientists using the image sensor see through the water as if it wasn’t there.

Tim Malthus from the CSIRO has been working on it for 10 years. “If you want to see the corals, the intervening water is an influence, and we’ve been developing algorithms to remove the influence of that water,” Malthus told Guardian Australia.

The planes will fly through six regions of the reef, stretching from Heron Island near the southern end all the way to the Torres Strait.

The team has already completed survey flights over Kaneohe Bay in Hawaii as a test and will fly over the Great Barrier Reef by the end of October. After that they will survey the main Hawaiian islands, Marianas islands and Palau.

The biggest promise the work holds out is in its future applications on satellites, Hochberg said.

A better way to understand reef health than a snapshot is to see how they change over time. Several groups plan to launch satellites with sensors that could produce this type of data. The Japanese space agency Jaxa is planning to launch HISUI in 2018 and the German Aerospace Laboratory is due to launch EnMap in 2019.

Nasa is considering one called HyspIRI, which is still in the conceptual stage.

According to Malthus, that will change the way coral reefs are studied. “This is really a precursor for the next generation of satellites that will be in space,” he said. “It allows us to prepare and explore new algorithms for when these types of sensors are routinely operated in space.”

Social Profiles