The United Nations has declared Sunday to be the International Day for Biodiversity to raise awareness of the extinction risk facing animals and plants. Nearly a third of all species are now endangered due to human activities. Later this year governments will meet to come up with a long-term plan to reverse the threat to life on Earth – in all its varieties – at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference in China.

What is biodiversity and why is it important?

Biodiversity is the variety of all life on Earth – animals, plants, fungi and micro-organisms like bacteria.

Animals and plants provide humans with everything needed to survive – including fresh water, food, and medicines.

However, we cannot get these benefits from individual species – we need a variety of animals and plants to be able to work together and thrive. In other words, we need biodiversity.

Plants are also very important for improving our physical environment – by cleaning the air we breathe, limiting rising temperatures and providing protection against climate change.

Mangrove swamps and coral reefs can act as a barrier to erosion from rising sea levels. And common trees found in cities such as the London plane or the tulip tree, are excellent at absorbing carbon dioxide and removing pollutants from the air.

How many species are at risk of extinction?

It is normal for species to evolve and become extinct over time – 98% of all species that have ever lived are now extinct.

However, the extinction of species is now happening between 1,000 and 10,000 times more quickly than scientists would expect to see.

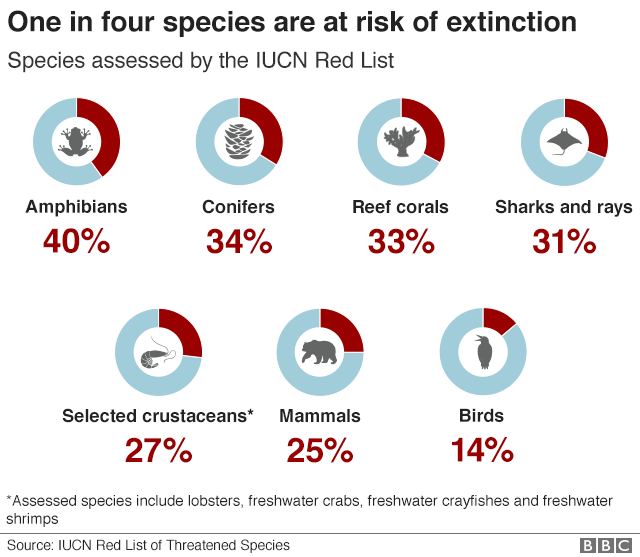

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has kept a “red list” of threatened species since 1964. More than 142,000 species have been assessed and 29% are considered endangered, which means they have a very high risk of extinction.

What are countries trying to agree in China?

It is hoped an agreement can be reached to stop what scientists are calling the “sixth mass extinction” event.

Governments will try to agree a long-term action plan – to be called the post-2020 Biodiversity Framework.

Its key aim is to slow down the rate of biodiversity loss by 2030, and to make sure that by 2050, biodiversity is “valued, conserved, restored… and delivering benefits essential for all people”.

What are the biggest threats to biodiversity?

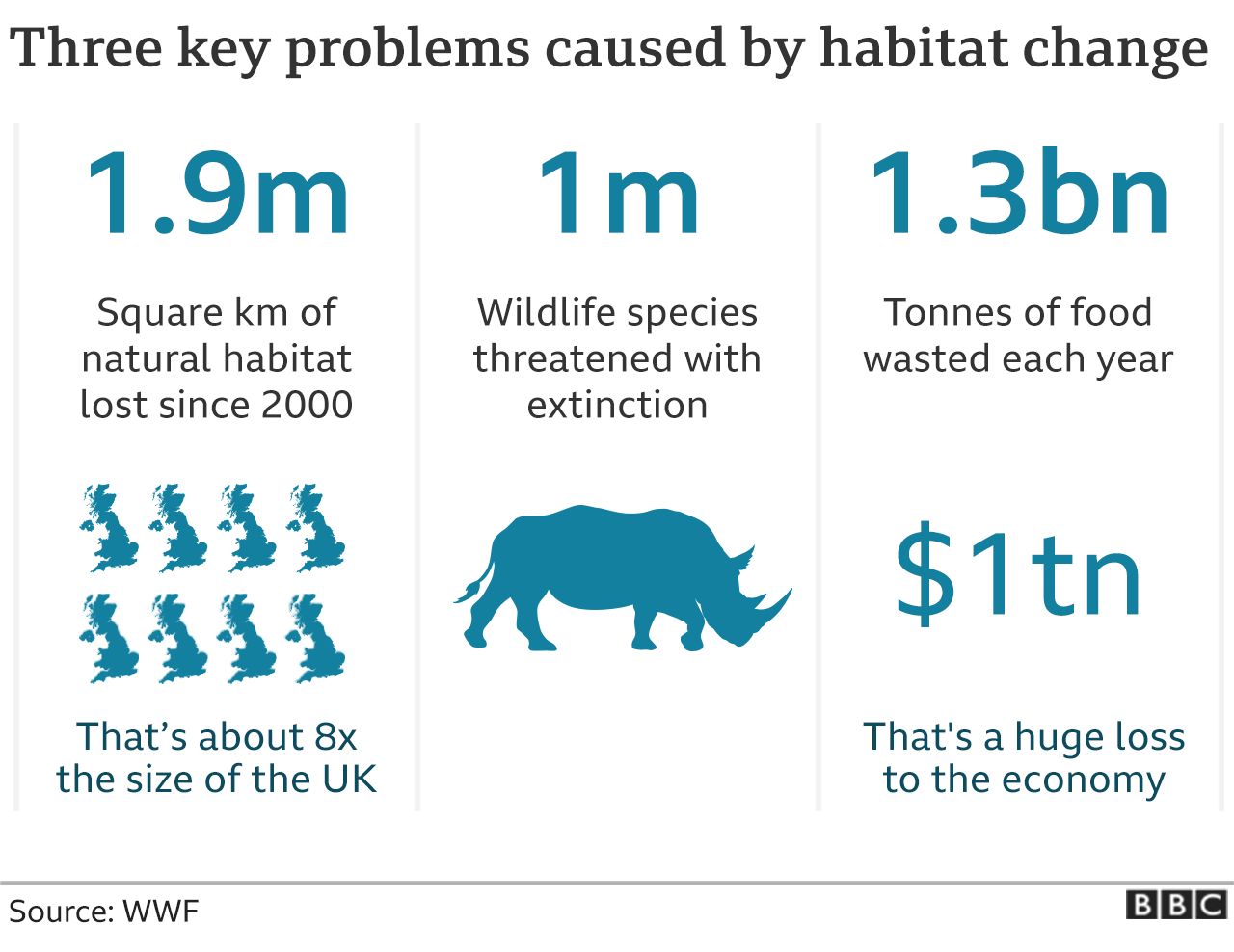

In 2019, a United Nations report said that harvesting, logging, hunting and fishing had all had an impact.

Between 2001 and 2020 the world lost 411 million hectares of tree cover – 16% of which was primary forest. These are very mature forests, which have taken hundreds – if not thousands – of years to develop. The destruction of these rich environments can have a very serious impact on biodiversity.

Biodiversity loss is occurring worldwide, but the Natural History Museum in London has found that Malta, the UK, Brazil and Australia have experienced the biggest changes – due to pollution, rapid industrialisation and over use of water.

Climate change is also difficult for animals and plants to adapt to, the UN warns.

It says species extinction would be lower if global warming was limited to 1.5°C.

What kind of action is being proposed?

The post-2020 framework has four goals:

- increased conservation

- resources used as sustainably as possible

- more equal sharing of natural resources

- increased financial support for biodiversity protection

It wants greater use of trees and plants to absorb carbon dioxide and balance out greenhouse gas emissions

However, the UN also warns that planting trees on landscapes where they have never been before could introduce invasive species, which “can have significant negative impacts on biodiversity”.

In order to achieve these targets governments and private organisations are pledging to give at least £152bn ($200bn) per year by 2030 – with 5% going to developing nations.

So far, the average spend has been £59bn – £69bn ($78bn-91bn) per year.

Social Profiles