The climate campaigner Greta Thunberg chose to sail to a UN climate conference in New York in a zero-emissions yacht rather than fly – to highlight the impact of aviation on the environment. The 16-year-old Swede has previously travelled to London and other European cities by train. Meanwhile the Duke and Duchess of Sussex have faced criticism over opting to fly to Sir Elton John’s villa in Nice in a private jet. So what is the environmental impact of flying and how do trips by train, car or boat compare?

What are aviation emissions?

Flights produce greenhouse gases – mainly carbon dioxide (CO2) – from burning fuel. These contribute to global warming when released into the atmosphere.

An economy-class return flight from London to New York emits an estimated 0.67 tonnes of CO2 per passenger, according to the calculator from the UN’s civil aviation body, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

That’s equivalent to 11% of the average annual emissions for someone in the UK or about the same as those caused by someone living in Ghana over a year.

Aviation contributes about 2% of the world’s global carbon emissions, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA). It predicts passenger numbers will double to 8.2 billion in 2037..

And as other sectors of the economy become greener – with more wind turbines, for example – aviation’s proportion of total emissions is set to rise.

How do emissions vary?

It depends where passengers sit and whether they are taking a long-haul flight or a shorter one.

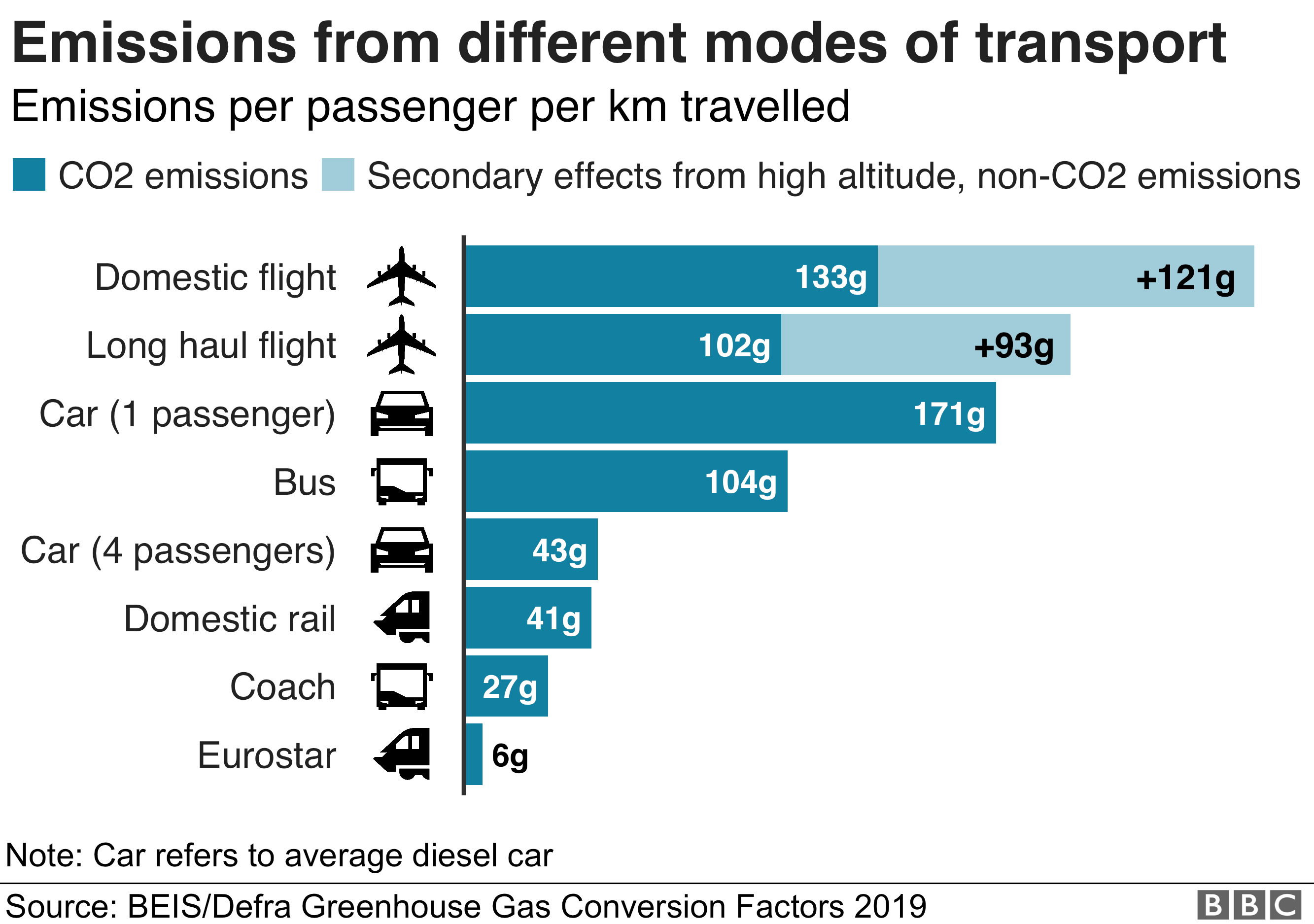

The flight figures in the table are for economy class. For long haul flights, carbon emissions per passenger per kilometre travelled are about three times higher for business class and four times higher for first class, according to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

This is because there’s more space per seat, so each person accounts for a larger amount of the whole plane’s pollution.

Taking off uses more fuel than cruising. For shorter flights, this accounts for a larger proportion of the journey. And it means lower emissions for direct flights than multi-leg trips.

Also, newer planes can be more efficient and some airlines and routes are better at filling seats than others. One analysis found wide variation between per passenger emissions for different airlines.

For private jets, although the planes are smaller, the emissions are split between a much smaller number of people.

For example, Prince Harry and Meghan’s recent return flight to Nice would have emitted about four times as much CO2 per person as an equivalent economy flight.

The increased warming effect other, non-CO2, emissions, such as nitrogen oxides, have when they are released at high altitudes can also make a significant difference to emissions calculations.

“The climate effect of non-CO2 emissions from aviation is much greater than the equivalent from other modes of transport, as these non-CO2 greenhouse gases formed at higher altitudes persist for longer than at the surface and also have a stronger warming potential,” Eloise Marais, from the Atmospheric Composition Group, at the University of Leicester, told BBC News.

But there is scientific uncertainty about how this effect should be represented in calculators.

The ICAO excludes it, while the BEIS includes it as an option – using a 90% increase to reflect it.

The EcoPassenger calculator – launched by the International Railways Union in cooperation with the European Environment Agency – says it depends on the height the plane reaches.

Longer flights are at higher altitude, so the calculator multiplies by numbers ranging from 1.27 for flights of 500km (300 miles) to 2.5 for those of more than 1,000km.

In the chart above, the high-altitude, non-CO2 emissions are in a different colour.

How does travelling by train compare?

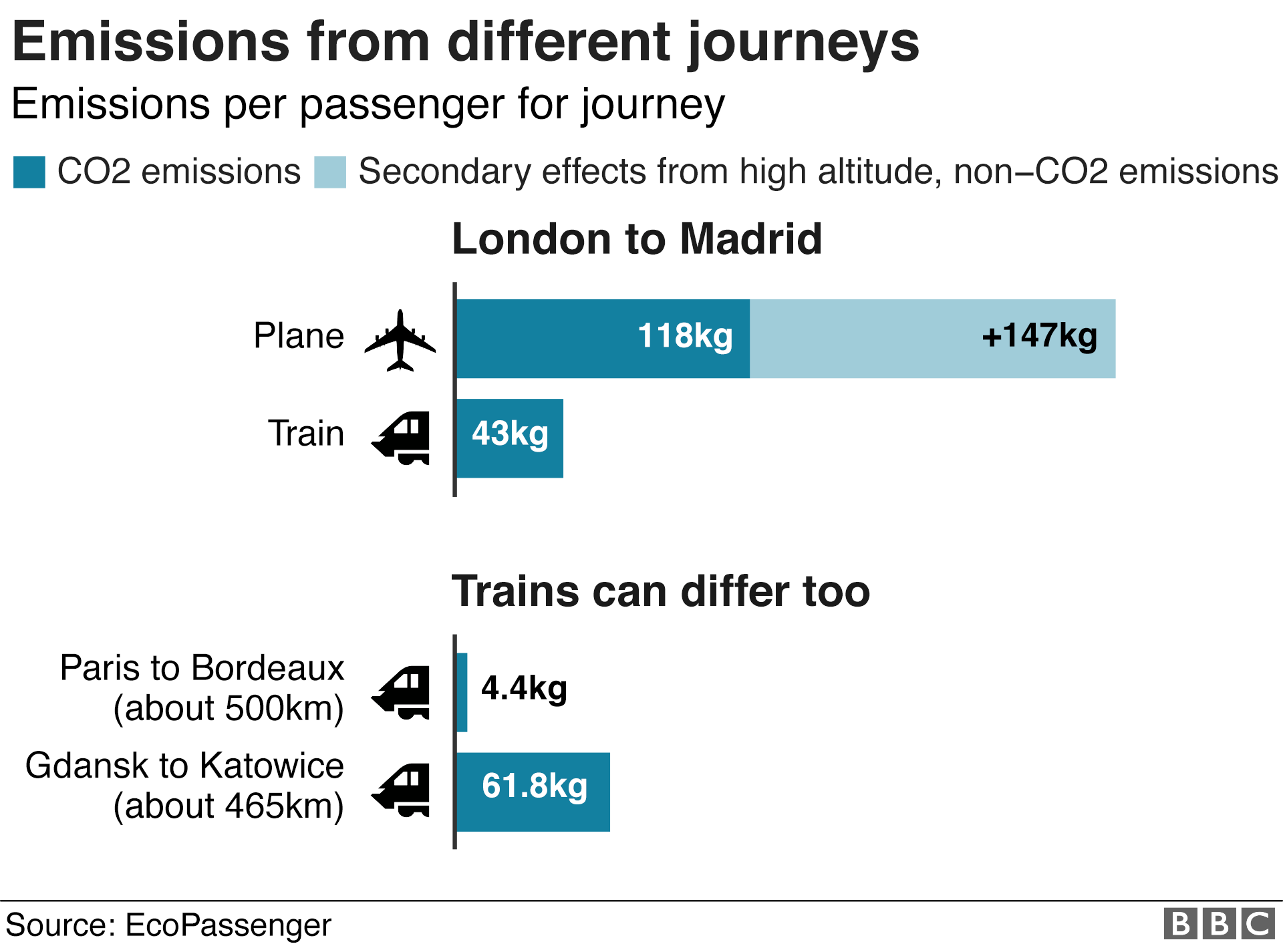

Train virtually always comes out better than plane, often by a lot. A journey from London to Madrid would emit 43kg (95lb) of CO2 per passenger by train, but 118kg by plane (or 265kg if the non-CO2 emissions are included), according to EcoPassenger.

However, the margin between train and plane emissions varies, depending on several factors, including the type of train. For electric trains, the way the electricity they use is generated is used to calculate carbon emissions.

Diesel trains’ carbon emissions can be twice those of electric ones. Figures from the UK Rail Safety and Standards board show some diesel locomotives emit more than 90g of C02 per passenger per kilometre, compared with about 45g for an electric Intercity 225, for example.

The source of the electricity can make a big difference if you compare a country such as France, where about 75% of electricity comes from nuclear power, with Poland, where about 80% of grid power is generated from coal.

According to EcoPassenger, for example, a train trip from Paris to Bordeaux (about 500km) emits just 4.4kg of carbon dioxide per passenger, while a journey between the Polish cities of Gdansk and Katowice (about 465km) emits 61.8kg.

As with plane journeys, another factor is how full the train is – a peak-time commuter train will have much lower emissions per person than a late-night rural one, for example.

Can driving be better than flying?

Yes, if the car’s electric – but diesel and petrol cars are also in many cases better options than flying, though it depends on various factors, particularly how many people they’re carrying.

According to EcoPassenger, a journey from London to Madrid can be done with lower emissions per passenger by plane, even accounting for the effect of high altitude non-CO2 emissions, if the car is carrying just one person and the plane is full. If you add just one more person into the vehicle, the car wins out.

Coaches also score well. BEIS says travelling by coach emits 27g of CO2 per person per kilometre, compared with 41g on UK rail (but only 6g on Eurostar) – though again this will vary depending on how full they are and the engine type.

What about travelling by boat?

The BEIS has also put a figure on ferry transport – 18g of CO2 per passenger kilometre for a foot passenger, which is less than a coach, or 128g for a driver and car, which is more like a long-haul flight.

But ferries’ ages and efficiency will vary around the world – and a ferry won’t get you to America, although a cruise ship or ocean liner would.

The cruise industry has long been under pressure to reduce environmental impacts ranging from waste disposal to air pollution, as well as high emissions – not only from travel but also from powering all the on-board facilities.

Carnival Corporation and plc, which owns nine cruise lines, says its 104 ships emit an average of 251g of carbon dioxide equivalent per “available lower berth” per kilometre.

And, while the figures are not directly comparable, they suggest cruising falls in similar territory to flying in terms of emissions.

Social Profiles