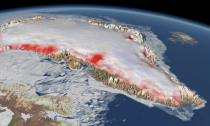

Greenland is losing ice seven times faster than it was in the 1990s. The assessment comes from an international team of polar scientists who’ve reviewed all the satellite observations over a 26-year period. They say Greenland’s contribution to sea-level rise is currently tracking what had been regarded as a pessimistic projection of the future.

It means an additional 7cm of ocean rise could now be expected by the end of the century from Greenland alone.

This threatens to put many millions more people in low-lying coastal regions at risk of flooding.

It’s estimated roughly a billion live today less than 10m above current high-tide lines, including 250 million below 1m.

“Storms, if they happen against a baseline of higher seas – they will break flood defences,” said Prof Andy Shepherd, of Leeds University.

“The simple formula is that around the planet, six million people are brought into a flooding situation for every centimetre of sea-level rise. So, when you hear about a centimetre rise, it does have impacts,” he told BBC News.

The British scientist is the co-lead investigator for Imbie – the Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise.

It’s a consortium of 89 polar experts drawn from 50 international organisations.

The group has reanalysed the data from 11 satellite missions flown from 1992 to 2018. These spacecraft have taken repeat measurements of the ice sheet’s changing thickness, flow and gravity. The Imbie team has combined their observations with the latest weather and climate models.

What emerges is the most comprehensive picture yet of how Greenland is reacting to the Arctic’s rapid warming. This is a part of the globe that has seen a 0.75C temperature rise in just the past decade.

The Imbie assessment shows the island to have lost 3.8 trillion tonnes of ice to the ocean since the start of the study period. This mass is the equivalent of 10.6mm of sea-level rise. What is more, the team finds an acceleration in the data.

Whereas in the early 90s, the rate of loss was equivalent to about 1mm per decade, it is now running at roughly 7mm per decade.

Imbie team-member Dr Ruth Mottram is affiliated to the Danish Meteorological Institute.

She said: “Greenland is losing ice in two main ways – one is by surface melting and that water runs off into the ocean; and the other is by the calving of icebergs and then melting where the ice is in contact with the ocean. The long-term contribution from these two processes is roughly half and half.”

In an average year now, Greenland sheds about 250 billion tonnes of ice. This year, however, has been exceptional for its warmth. In the coastal town of Ilulissat, not far from where the mighty Jakobshavn Glacier enters the ocean, temperatures reached into the high 20s Celsius. And even in the ice sheet interior, at its highest point, temperatures got to about zero.

“The ice loss this year was more like 370 billion tonnes,” said Dr Mottram.

Back in 2013, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – the authoritative body that reconciles all climate science – gave a mid-range projection for global sea level rise of about 60cm by 2100. A mixture of ice melt and expansion of warming water.

But when Imbie published its companion review of Antarctica in 2018, it found the White Continent’s contribution by 2100 was likely being underestimated by 10cm. Now, for Greenland, Imbie is saying the shortfall is 7cm. The IPCC will have to incorporate these updates when it releases its next major assessment report (AR6) of Earth’s climate in a couple of years’ time.

Prof René Forsberg, from the Technical University of Denmark, said the Imbie exercise underlined the importance of flying satellites, especially those that can observe the top of Greenland, higher than 83 degrees North. Only two of the present fleet can, and one of those spacecraft is operating beyond its design life.

“Most of the changes we’ve seen in Greenland have been in the west, south and east; and now it has slowly moved up to the north. So, yes, the next satellite in the European Union’s Copernicus programme needs to go to higher latitudes, and this is being discussed by the EU and the European Space Agency,” Prof Forsberg told BBC News.

The new satellite system – for the moment known as Cristal, but to be called a Sentinel if it flies – would be a radar altimeter to measure the changing shape of Greenland.

Imbie’s Greenland analysis is published in the journal Nature. Its release has been timed to coincide with the annual COP climate convention taking place this year in Madrid, and with the American Geophysical Union meeting here in San Francisco, where leading Earth scientists have gathered.

Social Profiles