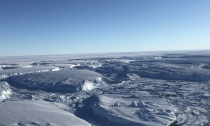

Earth’s great ice sheets, Greenland and Antarctica, are now losing mass six times faster than they were in the 1990s thanks to warming conditions. A comprehensive review of satellite data acquired at both poles is unequivocal in its assessment of accelerating trends, say scientists.

Between them, Greenland and Antarctica lost 6.4 trillion tonnes of ice in the period from 1992 to 2017.

This was sufficient to push up global sea-levels by 17.8mm.

“That’s not a good news story,” said Prof Andrew Shepherd from the University of Leeds in the UK.

“Today, the ice sheets contribute about a third of all sea-level rise, whereas in the 1990s, their contribution was actually pretty small at about 5%. This has important implications for the future, for coastal flooding and erosion,” he told BBC News.

The researcher co-leads a project called the Ice Sheet Mass Balance Intercomparison Exercise, or Imbie.

- Deepest point on land found in Antarctica

- ’56 lakes’ found under Greenland ice

- Journey to the ‘doomsday glacier’

It’s a team of experts who have reviewed polar measurements acquired by observational spacecraft over nearly three decades.

These are satellites that have tracked the changing volume, flow and gravity of the ice sheets.

Imbie’s Antarctica assessment was lodged with the journal Nature in 2018; its Greenland summary was published in the print edition of the periodical this week.

The team has used the latest milestone to offer some general remarks.

The key one is the recognition that ice losses are now running at the upper end of expectations when compared with the computer models used by the authoritative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

In the panel’s 2014 assessment, its mid-range simulations (RCP4.5) suggested global sea-levels might rise by 53cm by 2100. But the Imbie team’s studies show that ice losses from Antarctica and Greenland are actually heading to much more pessimistic outcomes, and will likely add another 17cm to those end-of-century forecasts.

“If that holds true it would put 400 million people at risk of annual coastal flooding by 2100,” said Prof Shepherd.

“What our latest estimates mean is that the timescales people are expecting will be shorter. Whatever town or coastal planning measures you’re intending to put in place, they need to be built sooner.”

Greenland and Antarctica are responding to climate change in slightly different ways.

The southern polar ice sheet’s losses come from the melting effects of warmer ocean water attacking its edges. The northern polar ice sheet feels a similar sort of assault but is also experiencing surface melt from warmer air temperatures.

Of that combined 17.8mm contribution to sea-level rise, 10.6mm (60 %) was due to Greenland ice losses and 7.2mm (40%) was due to Antarctica.

The combined rate of ice loss for the pair was running at about 81 billion tonnes per year in the 1990s. By the 2010s, it had climbed to 475 billion tonnes per year.

The delivery of the Imbie results was timed so they could be incorporated into the IPCC’s next big assessment of the state of Earth’s climate – the so-called Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) due out next year.

Prof Shepherd warns that future intercomparisons risk being of poorer quality because of the likely near-term demise of some dedicated polar satellites and the lack of clear and urgent plans to replace them.

His particular concern is to see successors to the European Space Agency’s CryoSat-2 satellite and the American space agency’s IceSat-2 platform.

These models observe more of the ice sheets than other satellites because they fly orbits that go very close to the north and south poles.

“I fear we will soon be back to the situation of the early 2000s when we had to make do with missions that were not really designed to look at polar regions. We’ll be doing our best despite the absence of the data we really require – unfortunately. But we’ve been there before.”

Social Profiles