Coral has been prized in Japanese jewellery since ancient times. As early as the Nara period, in the 8th century AD, the royal crown of Emperor Shomu and his Empress Komyo incorporated 10 hanging, red jewellery coral beads from the Mediterranean Sea.

With the depletion of the Mediterranean’s coral resources, Japan itself has increasingly become the main source of top-grade material, and an increasing demand from wealthy Chinese has encouraged poaching in Japanese waters.

The Japanese and Chinese governments recently agreed to work together to stamp out jewellery coral poaching from the waters of Okinawa – a rare case of co-operation between the two countries.

Hiroshi Hasegawa, an environmental chemistry professor at Kanazawa University on the Sea of Japan said there was a correlation between illicit fishing of jewellery corals and the rising affluence of Chinese consumers.

“Jewellery corals are very popular in China and Taiwan,” Hasegawa said.

Joji Shimajiri, senior fisheries supervising officer in Okinawa, said marine patrols had observed a huge increase in the number of fishing boats dredging up jewellery coral in the waters off Okinawa and other islands of Japan’s southern Ryuku archipelago in recent years.

Since last year, Japanese patrol ships have often sighted as many as 60 coral fishing boats at a time between Okinawa and Miyakojima Island and near Kumejima Island, Shimajiri said. In 2011, south of Kumejima, patrols sighted a fleet of 30 boats at work.

These are 100-tonne vessels, Chinese-flagged and with Chinese names, leaving little room for doubt about their nationality, Shimajiri said.

At an annual fisheries meeting between Japan and China in August, Japanese officials asked their Chinese counterparts to crack down on coral poachers. China had agreed to do so and said it was already bringing criminal prosecutions against illegal Chinese operators, said Akihiro Mizukawa, senior fisheries negotiator at the Japanese Fisheries Agency’s division of international affairs.

This was the first time Japan had brought up the problem with China in this way, Mizukawa said.

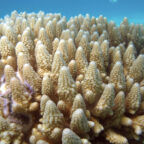

Unlike the shallow-water coral reefs that snorkellers or scuba divers love to explore, jewellery corals grow in relatively deep waters, usually over 30m below the surface, where sunlight barely penetrates.

The global wholesale market for jewellery corals is worth around US$50mil to US$60mil (RM155mil to RM190mil) a year, with Japan, Taiwan and Italy being the major producers.

“The price of jewellery coral varies widely, depending on the shade of colour, the size and the quality of the coral,” said Noriyoshi Yoshimoto, president of the Precious Coral Protection and Development Association, a non-profit environmental group in Tokyo.

A deep red variety, known as “oxblood” coral, now mostly purchased from Japan, is the most coveted, rarest and most expensive. Usually found around 110m below the surface, a top grade large oxblood coral in perfect condition, with no holes, marks or cracks can sell for as much as ¥20 million per kilogramme (RM636,690), or “about four times the price of pure gold,” Yoshimoto said.

The Japanese government has not been able to aggressively prosecute poachers because although they are operating in waters within Japan’s exclusive economic zone they are often doing so in an area agreed under the Japanese-Chinese fisheries pact to be neutral territory for fishing purposes.

Poachers are a particular problem because they not only harvest the corals illegally, but they do so in an aggressive and environmentally damaging way, Shimajiri, the Okinawa fisheries supervisor said.

Chinese poachers typically trawl for coral using drag nets that destroy the entire ecological system of the ocean floor around the coral reefs.

“We’ve been seeing the poachers use nets as long as 300m, width of 20m to 30m … and rocks the size of soccer balls attached at the end to weigh the nets down,” Shimajiri said.

By scraping the ocean floor, the Chinese vessels are destroying the habitat of highly prized fish, such as Japanese amberjack, or akamachi, and ruby snapper, another member of the grouper family, he added.

In contrast, Okinawa boats are under 20 tonnes in size and use unmanned vehicles to go deep in the ocean to pick out only fully grown corals. In fact, the Japanese coral industry is so tightly regulated that only one Japanese operator is allowed to harvest corals in the Okinawa area to avoid over-fishing, Shimajiri said.

Nozomu Iwasaki, a marine biology professor at Rissho University, said he witnessed what appeared to be a Chinese ship taking jewellery coral illegally. He said Taiwanese operators who used to poach jewellery coral some years ago may now be operating Chinese ships.

Chinese demand for jewellery corals is so high that 90% of corals harvested in Japan are now sold to China via Taiwan, Iwasaki said. He said prices had increased tenfold in the past nine years.

The Taiwanese government has been clamping down on illicit coral fishing since 2009, said Gary Sheu, director of the press and information division at the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office in Japan.

Transferring the ownership of Taiwanese vessels directly to Chinese operators is not permitted, and Taiwanese fishing vessels are prohibited by law from purchasing poached corals from Chinese operators. If such sales take place both parties are liable to prosecution, Sheu said.

Meanwhile, researchers including Iwasaki have been investigating just how much jewellery coral is growing in Japanese waters: accurate figures have not until now been available because of the extreme depth at which the coral grows.

Iwasaki and his team have been sending down remotely controlled underwater vehicles on week-long surveys, once or twice a year for the last seven years in the seas off Kochi, Kagoshima and Okinawa prefectures in southern Japan, charting 10 jewellery coral locations so far.

Social Profiles