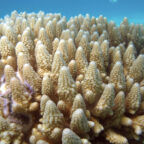

Local and international marine experts are joining forces in the ocean around Little Cayman on an important conservation project to try and understand and then save endangered local coral species. The plight of the now critically endangered staghorn coral, which was once one of the most abundant corals on Caribbean reefs, is at the top of the agenda. A mysterious die-off starting in the 1980s resulted in a loss of almost 90% of the population.

As a result both staghorn and elkhorn coral, in the genus Acropora, are listed as criticalely Endangered on the IUCN Red List of threatened species. The Central Caribbean Marine Institute and the Department of Environment have been using a grant from the Darwin Initiative to fund research on the biodiversity of coral and what they can do to increase this species.

This month, they begin a second phase which is simulating future potential stress to corals and other species.

“We are trying to understand how different corals might resist or adapt to changing ocean conditions” explains Dr Carrie Manfrino, a co-investigator with Tim Austin of the DoE on the Darwin grant. “In the first stage of the study, we have improved the odds of survival for the coral by testing different strategies for fragmenting the colonies. The second stage includes laboratory experiments simulating future increases in carbon dioxide in the ocean.”

With rising atmospheric carbon dioxide the oceans are absorbing a large share of this gas which results in a lowering of the ocean’s pH. This process is called Ocean Acidification.

“We are learning that certain areas of the reef might be more resistant to Ocean Acidification, but not for the reasons you might think. The current thinking is that sea grasses can absorb some of the carbon dioxide being pumped into the ocean because plants use CO2 during photosynthesis and give off oxygen. Currently, we suspect that higher night time respiration or lights out, no photosynthesis at night might be driving pH very high in lagoons where water circulation is stagnant.

“Having a very large range in pH – very acidic and very basic – seems to allow certain corals to thrive, while others suffer. The work is helping us understand interactions between ocean circulation and ocean acidification in a real world setting,“ explained Manfrino.

The research team currently in residence at Little Cayman Research Centre is working to understand how to improve the survival of corals under stress.

Protecting coral reefs for the future is CCMI’s most urgent mission, the officials said. With many factors contributing to the global decline in coral health, understanding interactions between water quality, wave exposure, human impacts, and the differences in the adaptability of corals is a continuing priority. CCMI’s research aims to determine which of these many factors are of important to driving coral resistance to stress.

This Darwin Initiative project in the Cayman Islands comes at a time when recent publication by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) throw new light on the state of coral reefs.

The “Status and Trends of Caribbean Coral Reefs: 1970-2012” report indicates that coral reef ecosystems in the Caribbean could be wiped out by 2035 without proper marine management and protection of endangered species. However, despite this overall downward trend coral cover, some reefs in the Cayman Islands are actually improving. Understanding the factors driving this recovery is obviously an urgent priority.

“We see a positive trajectory in coral cover since 2009 suggesting that low human impact and higher levels and larger areas of marine protection at Little Cayman may offer reefs some potential for buffering the effects of global change. However, we will need to examine specific factors that support coral recovery,” added Manfrino.

Social Profiles