Life is tough if you’re a blundering, buck toothed, bumphead.

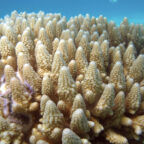

You’re far, far bigger than all the rest of the parrotfish in the Pacific. And weighing up to 45kg, you’re very popular at local birthdays and weddings. As the main course. So you console yourself with another chunk of crunchy coral reef! Tasty!

Ramming speed

These hapless hermaphrodites highlight a critical question in conservation. What do you do when an endangered species does things that are bad for the environment?

“They feed directly on these corals,” said Dr Douglas McCauley from the University of California in Santa Barbara who has studied and written about bumpheads extensively.

“They are big enough to ram into them, break off a piece and process this living rock. They eat tonnes of this living coral over the course of a year – they actually depress coral diversity.”

Coral are facing a whole reef-load of challenges, from warming, acidic oceans, to development and exploitation.

The last thing they need are hungry hordes of bumpheads, gorging on their very fabric.

But the big fish are not all bad news for the delicate underwater structures.

“These bumpheads are downright messy feeders, they break off dozens of pieces they don’t eat – those pieces are alive and we believe that acts as dispersal, like the way birds feed on fruits and disperse the seeds.”

Dr McCauley calls them “reef elephants”.

He says the comparison to the famed pachyderms of the Savannah is apt.

Both species are in the same category of threat. They both have massive impacts on their environments, and the outcomes are not always positive.

Dr McCauley says that sensitivities over the future of elephants and other creatures under threat mean that biologists are reluctant to highlight the cons as well as the pros.

“Someone could grab a one liner – bumpheads are bad for diversity, or elephants reduce forest structure, and run with that in dangerous ways.

“I think that is why there has been a bit of reluctance to report the positive and negatives – I think that while it is a more challenging task, I think the way forward is to seek to report the whole, complex story,” he argues.

One approach to conservation has been to designate national parks, in Africa and elsewhere.

But once elephant populations in these protected areas recover, they can become a threat to other species and biodiversity.

As with the bumpheads, how do you save the species without destroying the valuable ecosystem in which they live?

The answer is what’s termed “whole ecosystem management”, having an overview of the system and understanding the critical connections between the species.

In the case of the bumpheads, this means understanding the role of the coral reef and other species like sharks.

The finned predators can regulate the bumphead numbers, and help preserve the coral reefs as a side benefit.

The balance can be kept if you have enough sharks and enough bumpheads, which might be achieved through the introduction of marine protection zones. For these ocean dwellers, size really is everything.

“These creatures move large distances, ecosystems just don’t function anymore when we cut them down in size,” said Dr McCauley.

Despite the good intentions, getting more space in the seas or on land, is not easy.

Another approach is to use better information to refine protection to the really critical areas.

This is part of the thinking behind the African Raptor Databank, managed by a small Welsh consultancy called Habitat Info.

They’ve developed a mobile phone app that helps people in Africa record accurate details of sightings of vultures, buzzards and eagles and feed it into a live database. So far they’ve gathered 63,000 records of information.

Species like vultures have been reduced by 98% in West Africa, so those behind the project hope to identify the key “habitat strongholds” of these creatures, and inspire children and communities to help save these species.

The project is being financed by a number of groups including the Peregrine Fund.

Essentially they say that just like with the bumpheads, if you save the critical and sensitive species, you save a lot more besides.

“As widespread, far-ranging, top-of-the-food-chain predators, raptors have proven to be sensitive indicators of environmental change, especially contamination,” says Rick Watson, Vice President, of the Peregrine Fund.

“Likewise, by conserving sufficient habitat to sustain representative raptor species in the landscape, they can serve as umbrella species to conserve much of the associated biodiversity. And raptors’ functional roles in many ecosystems are essential for maintaining the balance of nature.”

Social Profiles