Off the coast of Southeast Florida, a mysterious new disease is killing coral reefs, turning them white and leaving nothing but a skeleton behind. More than half of the state’s 330-year-old Coral Reef Tract, which stretches across 175 miles in the Florida Keys, is infected with the disease. It’s called “white syndrome” by scientists because white stripes or spots cover the coral, and it was discovered in fall 2014.

Throughout 2017, the disease spread to a point where half the coral at some sites were affected, even some that had been considered the most resilient and important for reef building, according to a newsletter by the Southeast Florida Coral Reef Initiative, which helps raise awareness about Florida’s reefs.

The causes of the disease are still unknown, though researchers believe it may be due to a combination of factors, including water quality, said Ana Zangroniz, a Miami-Dade-based University of Florida Florida Sea Grant agent.

Coral reefs are important hotspots for many fish, producing almost one-third of the world’s marine fish species, despite covering only 1 percent of the ocean floor. Invertebrates such as jellyfish, lobster and crabs, fish, and sea turtles all rely on coral reefs for food, shelter or both, Zangroniz said.

“They are a major player in Florida tourism,” she said. “People come to South Florida from around the world to fish, snorkel, scuba dive, boat and enjoy the reefs.”

Important in Southeast Florida especially, the Coral Reef Tract also acts as a first line of defense against hurricanes or other major storms, sucking up energy to lessen their impact when they hit land, Zangroniz said.

The Coral Reef Tract is the third largest coral reef in the world, only after the famous Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia and the Belize Barrier Reef. It’s the only coral reef in the United States.

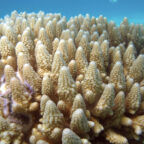

Before the new syndrome struck, coral had already been struggling because of coral bleaching, a problem worldwide. When water temperatures are too warm, corals expel the algae (zooxanthellae) that ordinarily live in their tissues and give coral its signature color. Bleaching causing the coral to turn completely white. The condition doesn’t kill the coral, but does leave it under stress.

Human activities that have added to worsening coral health include stormwater runoff, poor water quality, being hit by boat groundings and anchors, and coastal development, Zangroniz said.

While the bleaching weakens the coral, “white syndrome” is fatal.

The warming water that stresses the coral is due in part to human activity and climate change, said Tom Frazer, a professor and director of the School of Natural Resources and Environment.

Stopping coral bleaching has become more important than ever because white syndrome is spreading quickly, and coral dying on this scale could severely affect oceans and the animals that live in it.

Researchers believe identifying and selecting heat-resistant corals and having them replace dead reefs may be a solution, Frazer said.

But he said it’s not a permanent fix. Until the root causes of the disease are better understood, coral are likely to continue to suffer.

“Coral reefs harbor significant biodiversity in the world’s oceans,” Frazer said. “They are vibrant sources of tourism and support fisheries from all over the globe.”

Social Profiles