With satellites the size of a loaf of bread — and some artificial intelligence — scientists and researchers are mapping the world’s coral reefs in an effort to conserve and restore the marine organism.

Since its launch this past October, the Allen Coral Atlas has grown to include data from coral reefs across six geographic zones. As the project approaches its one year anniversary, members of the Allen Coral Atlas team gathered at Vulcan Inc.’s Seattle offices on Thursday to present findings and look ahead at what’s possible with the bank of images and corresponding data.

The project is an initiative of Vulcan, founded by the late Paul Allen, who was an avid diver and witnessed the threats to reefs firsthand. The atlas was unveiled just a couple of weeks after Allen’s death in October, following through on one of the late billionaire’s passions: preserving the world’s oceans. The Microsoft co-founder conceived of the Coral Atlas to document and monitor the condition of the globe’s coral reefs.

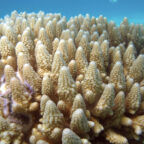

Reef ecosystems provide protection for thousands of species of fish and plant life, and serve as world-class tourist attractions. But they’re facing threats from climate change impacts such as warming ocean temperatures, as well as pollution and destructive fishing practices. In May, a U.N. report warned that nearly 33 percent of reef-forming corals are threatened with extinction.

Multiple university partners and research institutions are collaborating on the coral database, which is comprised of satellite imagery of tropical shallow coral reefs. The 3.7-meter resolution images form detailed maps of the reefs, including their depth and composition, and track changes driven by climate change and environmental factors. Vulcan and its partners aim to create a global map of coral reefs by the end of 2020.

Key to the project’s mission of saving the world’s coral is the ability for the maps to detect bleaching events, which kill algae and drain color from coral. Heatwaves in the ocean cause these thermal events that the scientific community has linked to climate change. However, the behavior of bleaching, such as the frequency, pattern and impact, remains unknown.

But the Allen Coral Atlas has the capability to unlock data around these events. For example, a sudden bleaching event occurred in French Polynesia last month.

“For the first time ever, we were able to track the bleaching event with our satellites that we’re using and at the same time, get in there with my field team, deploy to French Polynesia and measure the seafloor as it was bleaching,” recounted Greg Asner, a partner on the Allen Coral Atlas and director of the Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science at Arizona State University.

“For the first time in scientific history, we matched the scientific data to these field measurements,” he added. “It hasn’t been done before. That gives us the connection between what’s really happening on the seafloor as the hot water event occurs … the pattern and the biology of that process.”

These advancements have become possible thanks to the largest fleet of satellites ever assembled, courtesy of Planet, an Allen Coral Atlas partner. The hundreds of satellites deployed on this project exceed the collection operated by any organization, including NASA. Acquiring such a breadth of images on a daily basis creates a comprehensive view of the marine ecosystems.

Another factor is the evolution of AI. Asner’s team works with the latest AI to modify the images for scientific use, “to do things like digitally peel back the sea water so we can see the seafloor from these satellites — stuff that has not been possible until now,” he said.

The purpose of the maps is wide-ranging with overarching goals for conservation. Central to the project is the dissemination of coral reef data to local communities who can work to preserve regional ecosystems. It strengthens the data to collaborate with groups invested in the work at a grassroots level.

“That’s why it’s so important to combine local people because they love their reef even more than we do,” said Chris Roelfsema, an Allen Coral Atlas partner and senior research fellow at the University of Queensland in Australia.

Creating the most detailed, accurate maps is not only important as a monitoring tool. When regional partners have access to the data and maps, they can react quickly to events that could impact a reef, whether it’s a ship grounding, a bleaching event, weather, or a sedimentation event.

The maps also provide information critical to designing marine conservation plans. Data from the Allen Coral Atlas can help local groups establish coastal protected areas or work with policymakers to create new protections for reefs.

As the Allen Coral Atlas grows to cover more surface, the world’s reef communities gain new tools to help understand and care for their local ecosystems.

Other speakers at last week’s event included Vulcan’s Lauren Kickham; Planet’s Andrew Zolli; and Helen Fox from the National Geographic Society, another partner on the project.

In addition to the Allen Coral Atlas, Allen left a rich legacy of science projects ranging from the Allen Institute for Brain Science to the Great Elephant Census. He was a vocal advocate for open science, and in line with that stance, the Allen Coral Atlas will be freely licensed for non-commercial scientific and conservation uses.

Social Profiles