By any measure, the last 30 years have been utterly extraordinary. In less than one generation, our planet has changed faster than in all human existence. We have transformed from simple inhabitants of this world to the architects of its future. Nowhere is this more obvious than with tropical coral reefs.

I stumbled upon coral reefs on the shores of Arabia in 1982 as a 20-year-old. There my life changed forever in the moment I plunged from searing desert into the Red Sea, discovering myself surrounded by an impressionist riot. Fish as exotic as any jungle birds charged about purposefully, while others hung in roiling clouds above corals that plunged in petrified cascades into darkening depths. Reef life was richer, more prolific and urgent than anything I had seen.

For the next few years I followed the footsteps of great Arabian explorers, such as Lawrence and Burton, but going where they never could, often diving alone into seas teeming with sharks, turtles and flamboyant fish, unseen by any human eye. Tropical coral reefs are the richest and most prolific of all ocean habitats. A quarter of all shallow water species are here crammed into just a tenth of one per cent of the sea. What drove me then was a quest to unravel the secret of this enormous richness.

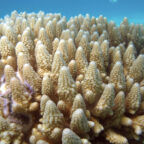

I thought that search would last a lifetime, but over the decades corals began to sicken and die across the world. My journey took a new direction, searching for the cause of their malaise and the hunt for a cure. It turns out that, although reefs have flourished for millions of years, creating geological structures so monumental they can be seen from space, they are incredibly sensitive to upset at the hands of people. We have turned up the thermostat on a world to which corals had become finely attuned. Global warming, in concert with more local pressures, such as overfishing and pollution, is killing coral.

The crux of their vulnerability lies in a 100-million-year long relationship between the coral animal and a microscopic plant, called zooxanthellae, that lives embedded in their tissues. Zooxanthellae gift corals the ability to live like plants, producing 85 to 95 per cent of their food by photosynthesis. In return, corals give the plants protection, nutrients and carbon dioxide, one of the ingredients for photosynthetic food production. It’s a wonderful relationship and is the secret of corals’ ability to build immense reefs, supercharging their productivity compared to creatures without zooxanthellae. But the partnership is fragile. When temperatures rise more than a degree or so above normal maxima, the relationship turns from benefit to deadly cost.

Since the late 1990s, across huge swathes of the tropics, coral reefs have suffered a catastrophic loss of life and vitality as corals have succumbed to a lethal cocktail of threats. Can anything be done to save them? The only durable fix will be a rapid reduction in greenhouse emissions to net zero. But even that won’t be enough, because carbon dioxide emissions have already overshot the coral comfort zone. We will need to suck some of it back too. That will take time, given political and societal headwinds slowing progress, so life will get harder for several more decades before it gets better.

In the meantime, we can give reefs a chance through better protection now. Just as a doctor would advise you to reduce stress, take more exercise and eat healthily to prevent sickness, reefs have a better chance of coping if we reduce overfishing, pollution and damage from tourism and development. We won’t be able to save coral reefs in their present form, except perhaps in a few fortunate places where conditions are unusually benign. For the rest, change is inevitable, perhaps drastically so. But the inevitability of coral loss need not be compounded by the predictably bad consequences of neglect. A well-protected reef will always be spectacular, thronging with fish and invertebrate life. I have swum on reefs where in the aftermath of destruction, less than one-twentieth of the seabed was covered in living coral. But benefitting nonetheless from strong protection, breathtaking schools of fish tens of thousands strong flowed above like shimmering rivers, almost concealing the bottom.

Coral reefs tell us something urgent and important about our head-long experiment in planetary remodelling: we need to change course now if we are to leave a world fit for generations yet to come. Coral reefs are just the first of many habitats that will suffer if we fail to rein in the greenhouse gases that driving temperatures up. But if we heed the coral warning now, we could spare nature and ourselves a great deal of suffering to come.

Callum Roberts is a professor of marine conservation at the University of York and author of Reef Life: An Underwater Memoir, out now from Profile Books. He is also the chief scientific advisor to BLUE Marine Foundation

Social Profiles