Coral bleaching affected 91% of reefs surveyed along the Great Barrier Reef this year, according to a report by government scientists that confirms the natural landmark has suffered its sixth mass bleaching event on record. The Reef snapshot: summer 2021-22, quietly published by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority on Tuesday night after weeks of delay, said above-average water temperatures in late summer had caused coral bleaching throughout the 2,300km reef system, but particularly in the central region between Cape Tribulation and the Whitsundays.

“The surveys confirm a mass bleaching event, with coral bleaching observed at multiple reefs in all regions,” a statement accompanying the report said. “This is the fourth mass bleaching event since 2016 and the sixth to occur on the Great Barrier Reef since 1998.”

It was the first mass bleaching event recorded during a cooler La Niña year.

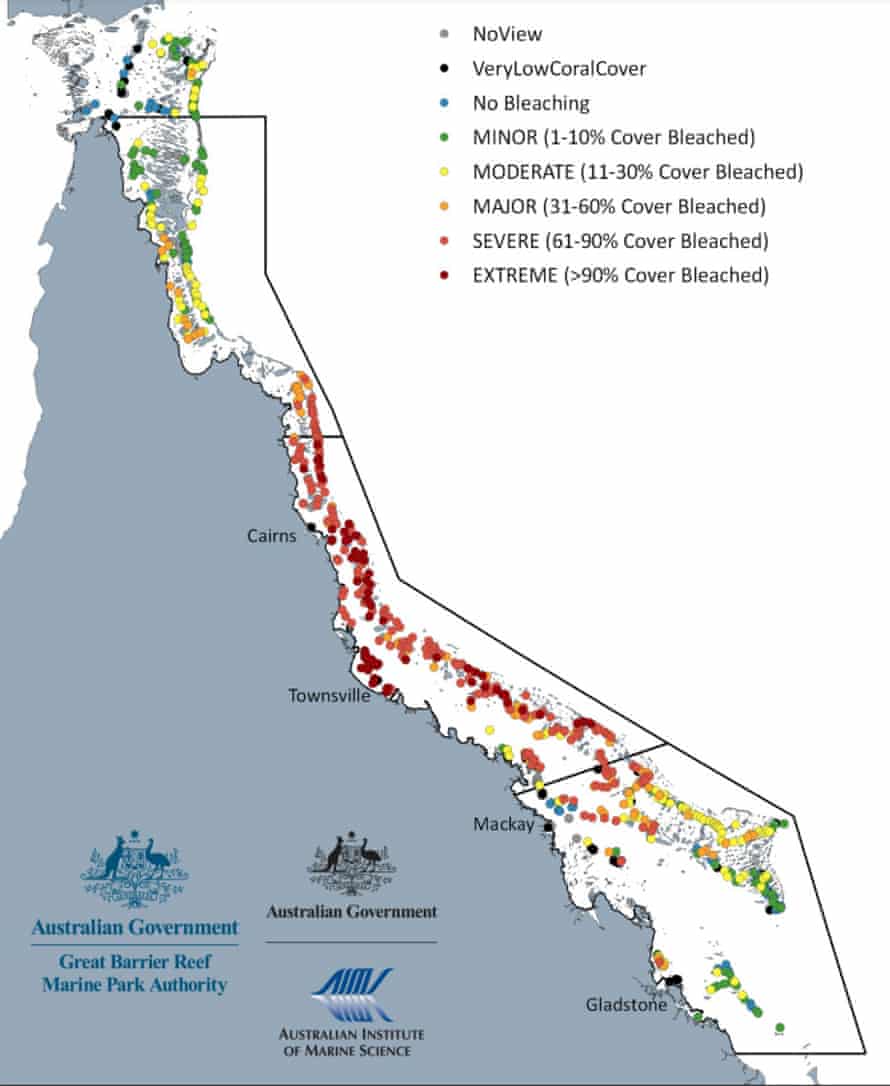

Scientists from the marine park authority and the Australian Institute of Marine Science surveyed 719 shallow water reefs between the Torres Strait and the Capricorn Bunker Group at the southern end of the reef system, mostly using helicopters. They found 654 reefs showed some bleaching.

A map published with the report shows the most severe and extreme bleaching occurred in the region that covers the areas most visited by tourists. The report said inshore and offshore reefs were badly affected.

Scientists from the marine park authority were not available to comment on the report on Tuesday night. The authority’s chief scientist, Dr David Wachenfeld, told the Guardian in March that bleaching was not expected in a La Niña.

“But having said that, the climate is changing and the planet and the reef is about 1.5 degrees centigrade warmer than it was 150 years ago,” he said. “Because of that, the weather is changing. Unexpected events are now to be expected. Nothing surprises me any more.”

Lissa Schindler, a campaign manager with the Australian Marine Conservation Society, said the report was “devastating news for anyone who loves the reef” and “yet more evidence” cutting fossil fuel emissions should be top priority for the next Australian government.

“This was a La Nina year, normally characterised by more cloud cover and rain,” she said. “It should have been a welcome reprieve for our reef to help it recover and yet the snapshot shows more than 90% of the reefs surveyed exhibited some bleaching.

“Although bleaching is becoming more and more frequent, this is not normal and we should not accept that this is the way things are. We need to break the norms that are breaking our reef.”

Schindler said while Labor had a commitment to make bigger emissions cuts by 2030 than the Coalition, neither party had targets in line with what would be needed globally to save the reef.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found limiting global heating to 1.5C rather than 2C would probably be the difference between the survival of some tropical reef corals and their complete decline. A report by Climate Analytics found the Coalition’s 2030 emissions reduction target was consistent with more than 3C of heating and Labor’s target about 2C.

The director of research at the Climate Council, Dr Simon Bradshaw, said: “This is an issue that cannot be solved with big shiny funding announcements. The science is very clear: in order to save the world’s reefs from total destruction, we must dramatically reduce emissions in the 2020s.”

Scientists started raising the alarm for this year’s bleaching event in December, when ocean temperatures over the reef hit a record high for that month.

Bleaching occurs when the coral becomes stressed from above-average water temperatures. The coral animal expels the photosynthetic algae that lives inside it and provides the coral with food and its colour.

Corals can survive bleaching events. Scientists plan to carry out in-water checks to see how many corals survived and regained their algae and colour between now and the end of the year.Advertisement

Studies have shown that heat stress can have several “sublethal” effects on corals, including making them more susceptible to disease, slowing their growth and limiting their ability to spawn.

The results of the surveys are expected to inform a report by a United Nations mission that visited the reef in March to check on its health and management. Scientists from Unesco and the International Union for Conservation of Nature were briefed on the surveys during the 10-day monitoring trip. Their report is due before the next world heritage meeting, currently scheduled for June.

Last year, scientific advisors at Unesco recommended the reef be placed on a list of world heritage sites “in danger” due to the impact of the climate crisis and slow progress on improving water quality. Sustained lobbying from the Morrison government led the 21-country committee to go against that advice.

The release of the report and maps follows scientists and conservationists calling on the marine authority to make them public. SBS reported that Paul Hardisty, the chief executive of the Australian Marine Institute of Science, had told a meeting of his staff that the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet advised releasing the survey results during the federal election campaign would have breached caretaker conventions.

Conservationists have also called on the government to release the state of the environment report, a five-yearly national assessment that has been sitting with the environment minister, Sussan Ley, since December.

Social Profiles