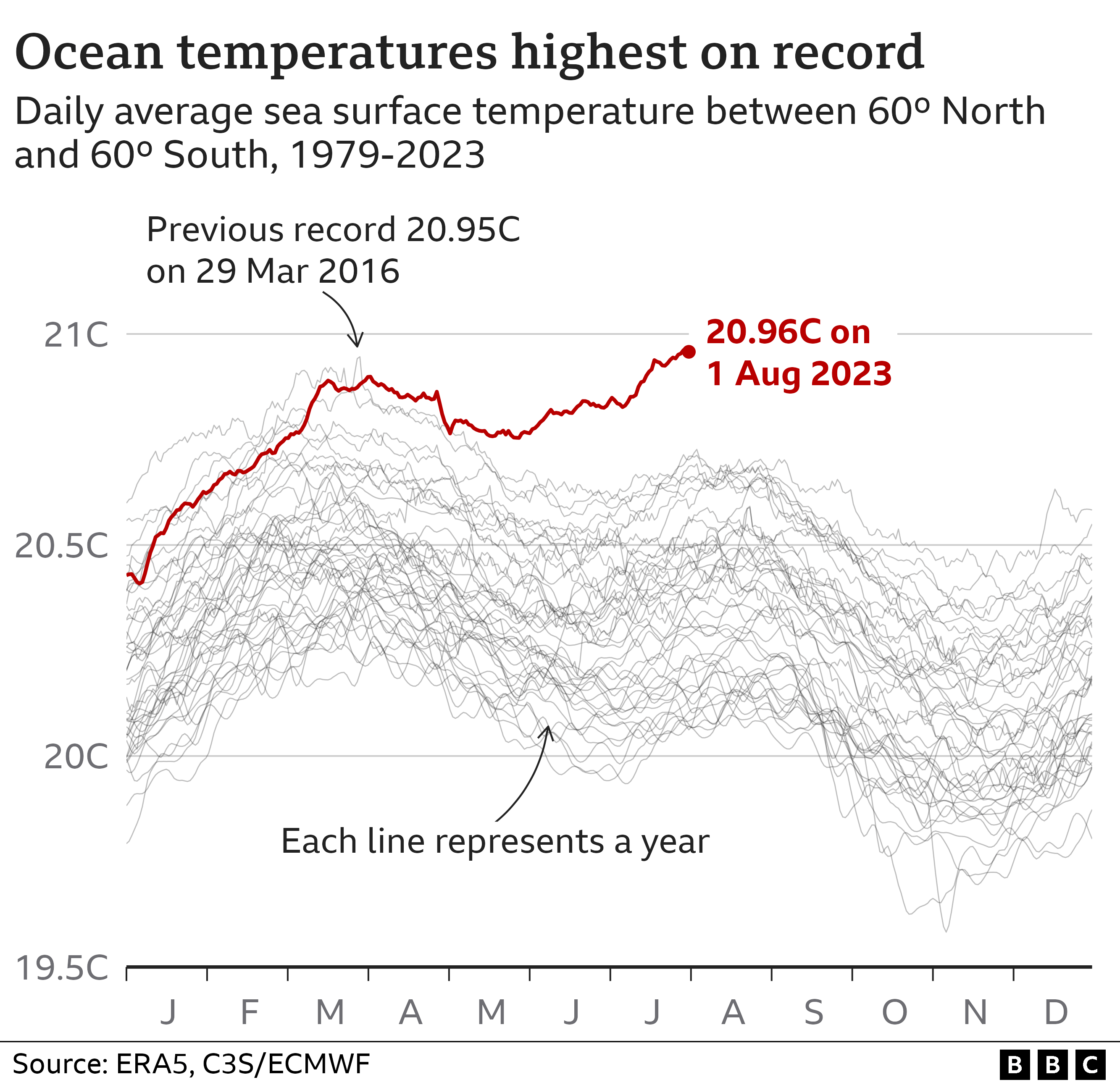

The oceans have hit their hottest ever recorded temperature as they soak up warmth from climate change, with dire implications for our planet’s health. The average daily global sea surface temperature beat a 2016 record this week, according to the EU’s climate change service Copernicus. It reached 20.96C. That’s far above the average for this time of year.

Oceans are a vital climate regulator. They soak up heat, produce half Earth’s oxygen and drive weather patterns.

Warmer waters have less ability to absorb carbon dioxide, meaning more of that planet-warming gas will stay in the atmosphere. And it can also accelerate the melting of glaciers that flow into the ocean, leading to more sea level rise.

Hotter oceans and heatwaves disturb marine species like fish and whales as they move in search of cooler waters, upsetting the food chain. Experts warn that fish stocks could be affected.

Some predatory animals including sharks can become aggressive as they get confused in hotter temperatures.

“The water feels like a bath when you jump in. Right now there is widespread coral bleaching at shallow reefs in Florida and many corals have already died,” says Dr Kathryn Lesneski, who is monitoring a marine heatwave in the Gulf of Mexico for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“We are putting oceans under more stress than we have done at any point in history,” says Dr Matt Frost from the Plymouth Marine Lab in the UK, referring to how pollution and overfishing also affect the oceans.

Scientists are also worried about the timing of this broken record.

“March should be when the oceans globally are warmest, not August or September. The fact that we’ve seen the record now makes me nervous about how much warmer the ocean may get between now and next March,” says Dr Samantha Burgess from the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

“It is sobering to see this change happening so quickly. We had a 247 day-long marine heatwave in the UK between August 2022 and April 2023,” says Prof Mike Burrows who is monitoring impacts on Scottish sea shores with the Scottish Association for Marine Science.

Scientists are investigating why the oceans are so hot right now but say that climate change is making the seas warmer as they absorb most of the heating from greenhouse gas emissions.

“The more we burn fossil fuels, the more excess heat will be taken out by the oceans, which means the longer it will take to stabilize them and get them back to where they were,” explains Prof Samantha Burgess.

The new average temperature record beats one set in 2016 when the naturally occurring climate fluctuation El Niño was in full swing and at its most powerful.

El Niño happens when warm water rises to the surface off the west coast of South America, pushing up global temperatures.

Another El Niño has now started but scientists say it is still weak – meaning ocean temperatures are expected to rise further above average in the coming months.

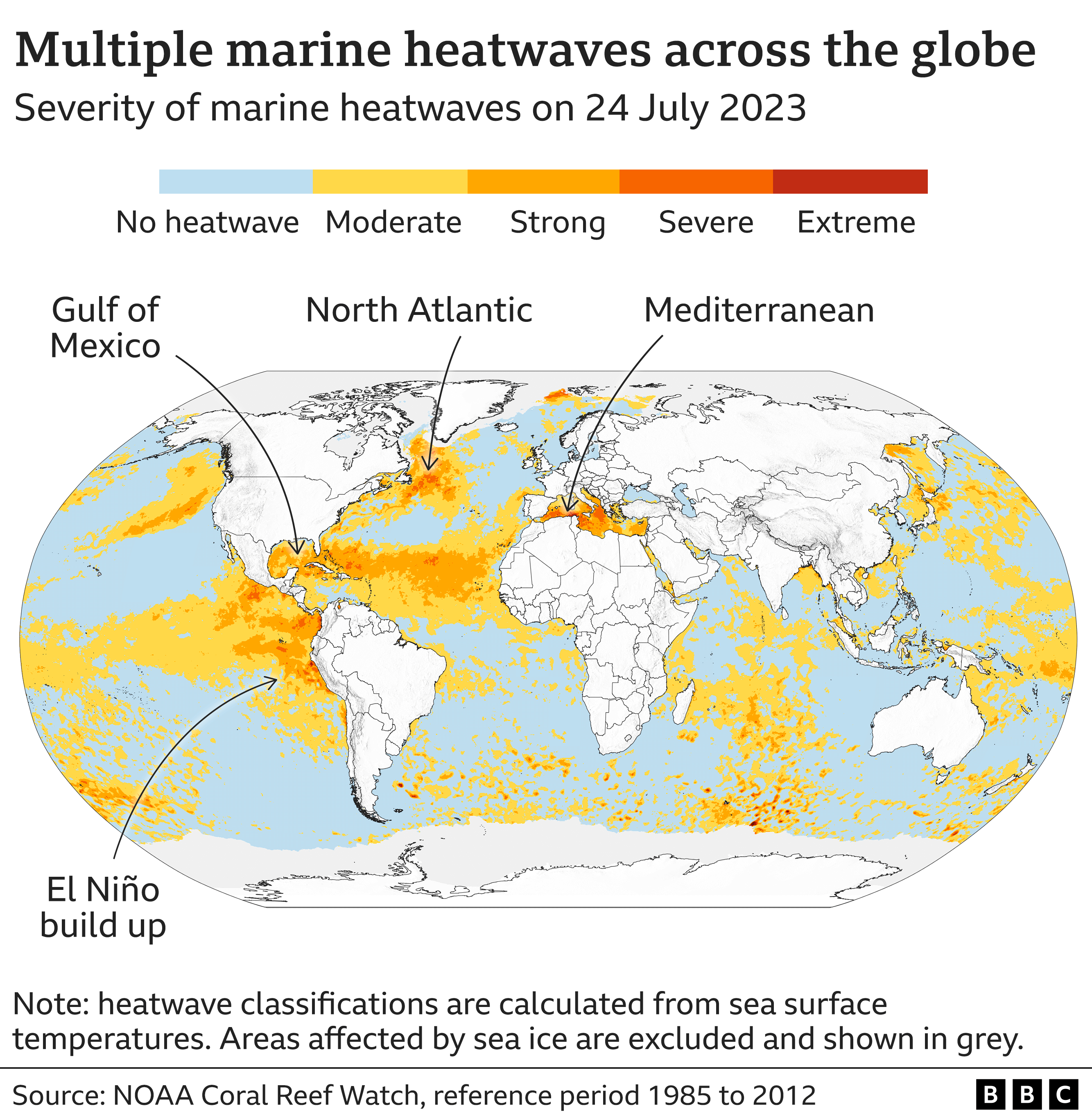

The broken temperature record follows a series of marine heatwaves this year including in the UK, the North Atlantic, the Mediterranean and the Gulf of Mexico.

“The marine heatwaves that we’re seeing are happening in unusual locations where we haven’t expected them,” says Prof Burgess.

In June, temperatures in UK waters were 3C to 5C higher than average, according to the Met Office and the European Space Agency.

In Florida, sea surface temperatures hit 38.44C last week – comparable to a hot tub. Normally temperatures should be between 23C and 31C, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Marine heatwaves doubled in frequency between 1982 and 2016, and have become more intense and longer since the 1980s, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

While air temperatures have seen some dramatic increases in recent years, the oceans take longer to heat up, even though they have absorbed 90% of the Earth’s warming from greenhouse gas emissions.

But there are signs now that ocean temperatures may be catching up. One theory is a lot of the heat has been stored in ocean depths, which is now coming to the surface, possibly linked to El Niño, says Dr Karina von Schuckmann at Mercator Ocean International.

While scientists have known that the sea surface would continue to warm up because of greenhouse gas emissions, they are still investigating exactly why temperatures have surged so far above previous years.

Social Profiles