An amazing project is unfolding in the remote Queensland town of Port Douglas which showcases the best science has to offer our society. They’re building a new ark for coral. And there isn’t a moment to lose. Great Barrier Reef Legacy, headquartered in Port Douglas, is working with Traditional Owners, industry and corporate partners, scientific collaborators, government organizations, and tourism operators to establish the world’s first Living Coral Biobank.

Like the mythical Noah’s ark, this project aims to conserve the genetic diversity of hard coral species and catalogue, collect, and store living fragments, tissue, and genetic samples from 400 coral species on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), and 400 coral species from all over the world.

Found worldwide, coral reefs are known to provide food, habitat, and a host of other ecological services. At least 25% of known marine species rely on tropical coral reef ecosystems, despite the habitat occupying less than 0.1% of the ocean floor; in fact, there are an estimated 1–9 million species that live in and around warm-water coral reefs.

There are numerous benefits that humans derive from coral reefs, too, including food, income, recreation, coastal protection, and having cultural importance to some communities. Yet anthropogenic activities are heavily affecting both warm- and cold-water coral reefs, despite their biological diversity, productivity, and importance. Consequently, coral reefs around the world are rapidly disappearing.

“With every coral bleaching event, we are losing the most vulnerable corals and coral reefs – with four mass bleaching events in just six years on the Great Barrier Reef, and over 50% of corals gone in the last few decades, we don’t have a moment to lose,” says Dr Dean Miller, managing director of Great Barrier Reef Legacy.

“The Living Coral Biobank Project buys us essential time in the face of global coral diversity and abundance loss.

“We will collect all known corals and keep them alive in land-based facilities for their ultimate conservation, and to aid in, and act as a catalyst, for reef research and restoration efforts.”

The project engaged Australian architects Contreras Earl Architecture with assistance from Arup and Werner Sobek, leading engineering and sustainability consulting firms, to make sure the state-of-the-art facility was not only able to keep corals alive but could also withstand natural disasters, like cyclones.

It is also carbon neutral, and has recently been honoured at the Energy Globe Awards for its innovative solutions integrating technology and ocean conservation.

“While we’ve designed the building with the corals in mind as the primary occupant, the 6,830sq m multi-function centre will also host exhibition areas, an auditorium and classrooms as well as advanced research and laboratory facilities over four levels,” says Rafael Contreras from Contreras Earl Architecture.

“Education and awareness is an important social aspect when we look at sustainable development, and the building’s distinctive sculptural form, inspired by mushroom coral, will help position it as a beacon for environmental awareness, and a centre for hope, learning and wonder.”

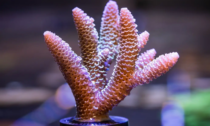

There are two types of coral: hard corals and soft corals, classified not only by their texture and composition but also by the number of tentacles that can be found on their adjoining polyps.

Often called reef-building corals, hard corals, like elkhorn coral and staghorn coral, exist in colonies. Their skeletons are composed of calcium carbonate, a substance created by thousands of individual polyps cemented together. The Great Barrier Reef has grown relatively quickly thanks to hard corals, while soft corals provide its food supply. For now, the focus is on preserving hard corals.

“Whilst we do have a long-term vision to collect soft corals, the immediate goal is to focus on the hard corals only. This is quite simply because without hard corals, there would be no coral reefs. They create the structure for all of the other living organisms of the reef to thrive on,” explains Great Barrier Reef Legacy Operations Manager, Paul Myers.

The project has already begun to collect samples to add to its database. “So far, we have 181 colonies in our collection, making it the most diverse coral collection on the planet – so far as we are aware,” says Myers.

“There has been no real prioritisation in collecting these samples, we have simply collected those most accessible to us,” he adds.

“As our collection grows, it will become more challenging to locate the rarest corals. With that being said, we have also already collected a few specimens that are new to the Great Barrier Reef. One particular coral in our collection, Echinopora robusta, is extremely rare andwas previously only confirmed to exist off the coast of Sri Lanka!”

Keeping wild corals alive during transit to the facility – and even in the tank – can be extremely difficult. Because they have adapted to specific oceanic conditions, they are vulnerable to changes in water salinity or temperature, which can quickly make them ill, lose their colour, and eventually die. Myers points out that the aquarium trade has been keeping corals alive in tanks for decades, which is why the project has partnered with several organisations that have the knowledge and experience to care for the collected corals.

Under ideal conditions, corals in aquariums can grow at a rate that far exceeds their growth rate in the wild.

“By pairing with the aquarium industry, we have tapped into the existing coral take quota and we are diverting what would have been sold in the aquarium trade, into our Project instead,” says Myers.

“Whilst we hope that it never comes to this, if it was needed, our corals can be tracked back to where they came from and could be used to enhance restoration efforts on the Reef.”

For the next two years, the focus will be on collecting and maintaining all Great Barrier Reef hard corals (about 400 species). The initial goal is to collect one specimen of every species from the Great Barrier Reef and then collect additional specimens of each species to preserve the genetic diversity within the species.

“For example, the same species of coral may be found in the Far Northern Reefs where temperatures are warmer, as well as being found in the cooler waters of the Far Southern Reefs. These will have slight genetic differences to help them survive in their local environment,” says Myers.

By 2026, the team hopes to not only have the full Living Coral Biobank facility built, but also collect and maintain 800 species of hard coral.

“Once we have the full collection, our fragments will double in size every year and can be re-fragmented. This means that we have a continuous supply of coral stock that can be used as a catalyst for reef research and restoration efforts, with no need for additional collections,” says Myers.

The project is also working with Traditional Owners to create Biobank ‘hubs’ along the coast of the Great Barrier Reef, with Traditional Owner’s from each region looking after a collection of corals in their section of the GBR. The hope is that hubs will be erected worldwide in areas that have reefs such as Fiji, Florida, and Hawaii.

You need not be a scientist to help with this project, as the public can donate funds to sponsor an expedition or tank. Alternatively, you can adopt a coral fragment and find out what species it is, where it was collected, and its growth and health information as it grows.

Social Profiles