The quest to compile the definitive map of Earth’s ocean floor has edged a little nearer to completion. Modern measurements of the depth and shape of the seabed now encompass 20.6% of the total area under water. It’s only a small increase from last year (19%); but like everyone else, the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project has had cope with a pandemic. The extra 1.6% is an expanse of ocean bottom that equated to about half the size of the United States.

The progress update on Seabed 2030 is released on World Hydrography Day.

The achievement to date still leaves, of course, four-fifths of Earth’s oceans without a contemporary depth sounding. But the GEBCO initiative is confident the data deficit can be closed this decade with a concerted global effort.

“It doesn’t matter whether you operate a high-tech fleet of ships or you’re just a simple boat-owner – every piece of data matters in this giant jigsaw we’re making,” said project director, Jamie McMichael-Phillips.

“If you’re going to sea for whatever reason, switch on your echosounder. Even if you’re just a yachtsman, a recreational sailor – then low-tech data-logging equipment is only a few hundred dollars, with the price coming down all the time. Fit it, plug in your GPS, plug in your echosounder and help us get to 100% coverage by 2030,” he told BBC News.

When Seabed 2030 was launched in 2017, only 6% of the oceans had been mapped to modern standards. So, it is possible to make swift and meaningful gains.

For example, a big jump in coverage would be achieved if all governments, companies, and research institutions released their embargoed data. There’s no estimate for how much bathymetry (depth data) is hidden away on private web servers, but the volume may be very considerable indeed.

Those organisations holding such information are being urged to think of the global good and to hand over, at the very least, de-resolved versions of their proprietary maps.

Seabed 2030 is not seeking 5m resolution of the entire floor (close to something we already have of the Moon’s surface). One depth sounding in a 100m grid square down to 1,500m will suffice; even less in much deeper waters.

The past 12 months have been hampered by the limitations Covid has placed on research cruises. This is unfortunate because it’s the science expeditions that will often visit those parts of the oceans where few other ships venture – into the Southern Ocean, for example.

That said, there’ve been some notable contributions of late from the research sector.

One of the most significant has come from the DSSV Pressure Drop, a ship funded by the Texan billionaire and adventurer Victor Vescovo.

His expeditions to the very deepest parts of Earth’s oceans mapped an area equivalent to the size of France in just 10 months (an area the size of Finland within this had never been seen before).

Better seafloor maps are needed for a host of reasons.

They are essential for navigation, of course, and for laying underwater cables and pipelines.

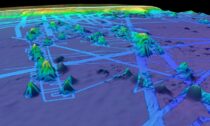

They are also important for fisheries management and conservation, because it is around the underwater mountains that wildlife tends to congregate. Each seamount is a biodiversity hotspot.

In addition, the rugged seafloor influences the behaviour of ocean currents and the vertical mixing of water. This is information required to improve the models that forecast future climate change – because it is the oceans that play a pivotal role in moving heat around the planet.

If Seabed 2030 is to meet the end-of-decade target, it will have to leverage the emergence of robotic ships and boats.

Uncrewed Surface Vessels (USVs) are becoming increasingly popular.

Fugro, one of the world’s leading marine geophysical survey companies, is building a fleet of USVs based on the Ocean X-Prize-winning SeaKit roboboat.

Fugro has two such boats surveying and inspecting oil-and-gas, wind farm, and power installations – in European waters and off Western Australia. Together, they are known as the Blue Essence fleet. These boats will even deploy and recover robotic subs.

“These drone-type, or uncrewed-type, solutions will make it easier to gather more data. They can do a lot more work in the same amount of time,” said Ivar de Josselin de Jong, Fugro’s solution director for remote inspection.

“Technology is moving very fast. It’s unbelievable what we do now compared with what we did 10 years ago.

“We can operate a USV in Australia from our remote operations centre in Aberdeen.

“We’ve got 26 crewed vessels at the moment and we want to gradually replace them – partially at least. Where we don’t need ‘hands’ in an offshore environment, we will move to uncrewed solutions, to reduce the health and safety exposure and to reduce carbon footprints,” he told BBC News.

To mark World Hydrography Day, The Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project has entered a technical cooperation agreement with the UK Hydrographic Office and Teledyne CARIS, a leading developer of marine mapping software. Building the definitive map of Earth’s ocean floor means collating colossal volumes of data. The new tie-up will see a new artificial intelligence tool being used to clean bathymetric data of “noise”, making it easier to pull out reliable depth soundings.

Social Profiles