Des and Kelvin of Gladstone, Katy and Filimone of Fiji and Victor and Christina of Palau all have the same issue – reefs under their care face unprecedented threats. Reefs that have protected shores and supported local fisheries for thousands of years. Fisheries sustained through customary management rooted in traditional ecological knowledge accumulated over millennia, reflecting local peoples’ deep understanding of their ecosystems.

They are not alone – the Pacific is home to 27% of the world’s coral reefs and her island nations are particularly reliant on healthy oceans for food, income and coastal protection, says Dr Manuel Gonzalez-Rivero, Australian Institute of Marine Science.

New understandings and tools are needed to manage reef-bound islands and coastlines facing challenges such as coral bleaching, macroalgal (seaweed) overgrowth, sea level rise, disease, predation, overfishing, pollution and marine debris.

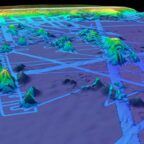

ReefCloud, is one of those new tools. The free-to-use platform was co-founded by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and targets the time-consuming analysis of reef survey imagery.

Reef Monitoring

Researchers monitoring reefs commonly swim transects taking photos. A transect is a line between two points; on a reef it might be marked by a tape stretched between pegs hammered into the bottom to make sure the same track is measured each time. Each photo usually covers a square metre of the bottom. Standardisation is critical in research.

Individual photos are then manually analysed, using programs such as Coral Point Count. Random points are assigned to each photo and the coral species and condition identified and coral cover calculated using Windows Excel.

Des Purcell, Gidarjil Ranger Co-ordinator, started using Coral Point Count in 2019 to monitor eighteen sites throughout the Port Curtis Coral Coast Native Title Claim, near Gladstone, Queensland.

Gidarjil Senior Sea Ranger Kelvin Rowe has spent days on a SCUBA taking photos on five transects per site, producing 4,500 photos each year for analysis. That’s a lot of hours staring at a screen. But this year the Rangers switched to ReefCloud.

ReefCloud uses facial recognition software to learn what a given coral looks like in a photo, and the next time that species appears, the AI recognises and counts it. Using machine-learning, the ReefCloudalgorithm was initially trained on millions of data points from annual image-based surveys of 80 reefs on the Great Barrier Reef – part of the AIMS Long-Term Monitoring Program.

Users upload images to the ReefCloud website, having accurately labelled a proportion of their images to contribute to training the model in the specifics of their site. The output they receive is a spreadsheet with the proportions of different species detected in each photo.

As Gonzalez-Rivero, AIMS’s Research Team Lead and ReefCloud Director, says, they made the software openly available to allow any users to photograph the reefs, collect that information, then use the AI to analyse the data. Summarised information is then packaged so it is easy to communicate where the problem is and what the causes are, and which actions should be priorities.

ReefCloud machine-learning improves standardisation, and coral reef composition is analysed with 80-90% accuracy, 700 times faster than manual assessment.

Familiarisation

AIMS is working with partners in Brunei, the Philippines, Vietnam, the Maldives, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Fiji, and other countries, to familiarise researchers, government officials and communities with the program. Dr Ashton Gainsford, Coral Reef Ecologist at AIMS says it’s about “building capacity in coral reef monitoring and including others in the ReefCloud framework in a collaborative way.

“Data are often centralised, in institutions, countries and regions, and this provides a way to share information more readily, so that decisions can be made using more accurate and standardised data,” Gainsford says.

“AIMS also works with local communities to exchange traditional knowledge and systems with partners and working on building that into a framework and into monitoring.”

But there are significant challenges here.

Recoding

Recoding has slowed uptake. Coral Point Count (CPC) codes for each species are not compatible with ReefCloud, so the tens of thousands of photos from older surveys must be recoded to fit into the AI. “It’s just easier to use the program [Coral Point Count] we are using now”, says Christina Muller Karanassos, Researcher at the Palau International Coral Reef Center (PICRIC), “although having this tool would definitely reduce the workload”, she adds. Three hundred and forty coral and volcanic islands comprise the Palau Archipelago, 650km north of Papua New Guinea.

Victor Nestor, also of PICRIC, and current leader of their ReefCloudproject, agrees: “We have 23 sites and then we get the three or even four staff that work and the CPC and it takes a lot of time. With ReefCloud it can be a lot quicker and just requires somebody to upload the photos and do some of the points and then the programme just runs it for you. We will definitely use the program for the 2024 survey period”, Nestor says.

Common language and labels

Common names of coral species also vary with country, potentially adding a layer of confusion to ReefCloud labelling. Gainsford, who works with researchers and communities as a ReefCloud trainer and facilitator, says: “We also need to standardise what labels we give to species within ReefCloud, making sure we’re talking about the same thing, so we can compare them.

“Users have their own labels for coral species within their own country’s projects, but each label is connected to a global label which all researchers understand and can translate for their own projects.”

Language and cultural barriers are also challenging, says Gainsford. The ReefCloud team applies a “bespoke” response to each country because of the “different governance structures in place that need to be appreciated and understood. We collaborate with government at different levels in-country,” says Gainsford.

Customary management

Customary management of fisheries by Pacific nations is rooted in traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and is currently practiced on some, but not all islands.

Where practiced, this might mean seasonal bans on harvesting or temporary fishery closures, or restrictions on which fish can be targeted, where and by whom. It often reflects localised (i.e. village level) community consensus.

Fiji’s Vetavura Foundation, based on the islands of Kaibu, Vatuvara, Kanacea and Adavaci in northern Lau, about 240km northeast of Fiji’s capital, Suva, has worked with AIMS to adapt their reef monitoring methods to include ReefCloud this year. Surveys are undertaken in partnerships with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). The entire community is involved in decision-making which may, for example, include the placing of fishing restrictions on areas to protect fish populations.

For example, the plight of sleeping Parrotfish and Kawakawa (Grouper) are of concern due to the increasing use of underwater lights and spearguns for night fishing in the lagoons, says Filimone Mate, Marine Researcher at the Vetavura Foundation.

With the ease of bagging a good meal increasing the popularity of the practice, populations of favoured species are declining. Such herbivorous fish are also important to maintain grazing pressure on marine algae to prevent mats smothering the reef. Add climate change-related marine heatwaves in this enclosed and already-vulnerable lagoon, and community-level management and tools such as ReefCloudbecome very useful.

As Katy Miller, Director of the Vatuvara Foundation says, “it is important to recognize how Pacific Islanders are implementing community adaptation and ecosystem management measures through revitalizing traditional practices and customs combined with innovative solutions to build resilience to the impacts of climate change.”

Managing local marine protected areas are an essential part of the adaptation process, she says.

More than 35 countries are already using ReefCloud, with close to 2 million images submitted from countries around the world, says Gonzalez-Rivero. AI is making it significantly easier to get through the mass of survey images and extract the information needed to advise communities and governments on the state of their reefs.

Social Profiles